14 Work and Potential Energy (conclusion)

Work and Potential Energy (conclusion)

14–1Work

In the preceding chapter we have presented a great many new ideas and results that play a central role in physics. These ideas are so important that it seems worthwhile to devote a whole chapter to a closer examination of them. In the present chapter we shall not repeat the “proofs” or the specific tricks by which the results were obtained, but shall concentrate instead upon a discussion of the ideas themselves.

In learning any subject of a technical nature where mathematics plays a role, one is confronted with the task of understanding and storing away in the memory a huge body of facts and ideas, held together by certain relationships which can be “proved” or “shown” to exist between them. It is easy to confuse the proof itself with the relationship which it establishes. Clearly, the important thing to learn and to remember is the relationship, not the proof. In any particular circumstance we can either say “it can be shown that” such and such is true, or we can show it. In almost all cases, the particular proof that is used is concocted, first of all, in such form that it can be written quickly and easily on the chalkboard or on paper, and so that it will be as smooth-looking as possible. Consequently, the proof may look deceptively simple, when in fact, the author might have worked for hours trying different ways of calculating the same thing until he has found the neatest way, so as to be able to show that it can be shown in the shortest amount of time! The thing to be remembered, when seeing a proof, is not the proof itself, but rather that it can be shown that such and such is true. Of course, if the proof involves some mathematical procedures or “tricks” that one has not seen before, attention should be given not to the trick exactly, but to the mathematical idea involved.

It is certain that in all the demonstrations that are made in a course such as this, not one has been remembered from the time when the author studied freshman physics. Quite the contrary: he merely remembers that such and such is true, and to explain how it can be shown he invents a demonstration at the moment it is needed. Anyone who has really learned a subject should be able to follow a similar procedure, but it is no use remembering the proofs. That is why, in this chapter, we shall avoid the proofs of the various statements made previously, and merely summarize the results.

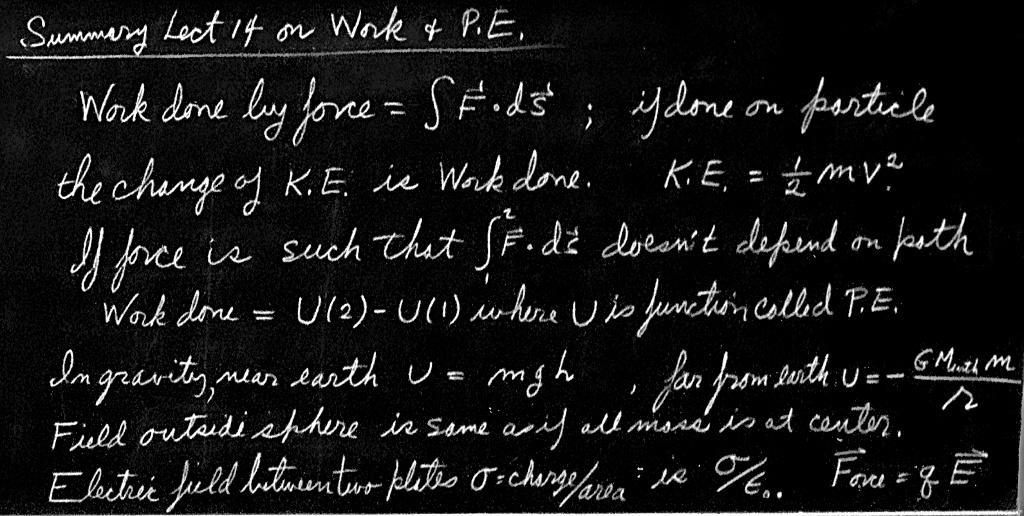

The first idea that has to be digested is work done by a force. The physical word “work” is not the word in the ordinary sense of “Workers of the world unite!,” but is a different idea. Physical work is expressed as $\int\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs$, called “the line integral of $F$ dot $ds$,” which means that if the force, for instance, is in one direction and the object on which the force is working is displaced in a certain direction, then only the component of force in the direction of the displacement does any work. If, for instance, the force were constant and the displacement were a finite distance $\Delta\FLPs$, then the work done in moving the object through that distance is only the component of force along $\Delta\FLPs$ times $\Delta s$. The rule is “force times distance,” but we really mean only the component of force in the direction of the displacement times $\Delta s$ or, equivalently, the component of displacement in the direction of force times $F$. It is evident that no work whatsoever is done by a force which is at right angles to the displacement.

Now if the vector displacement $\Delta\FLPs$ is resolved into components, in other words, if the actual displacement is $\Delta\FLPs$ and we want to consider it effectively as a component of displacement $\Delta x$ in the $x$-direction, $\Delta y$ in the $y$-direction, and $\Delta z$ in the $z$-direction, then the work done in carrying an object from one place to another can be calculated in three parts, by calculating the work done along $x$, along $y$, and along $z$. The work done in going along $x$ involves only that component of force, namely $F_x$, and so on, so the work is $F_x\,\Delta x + F_y\,\Delta y + F_z\,\Delta z$. When the force is not constant, and we have a complicated curved motion, then we must resolve the path into a lot of little $\Delta\FLPs$’s, add the work done in carrying the object along each $\Delta\FLPs$, and take the limit as $\Delta\FLPs$ goes to zero. This is the meaning of the “line integral.”

Everything we have just said is contained in the formula $W=\int\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs$. It is all very well to say that it is a marvelous formula, but it is another thing to understand what it means, or what some of the consequences are.

The word “work” in physics has a meaning so different from that of the word as it is used in ordinary circumstances that it must be observed carefully that there are some peculiar circumstances in which it appears not to be the same. For example, according to the physical definition of work, if one holds a hundred-pound weight off the ground for a while, he is doing no work. Nevertheless, everyone knows that he begins to sweat, shake, and breathe harder, as if he were running up a flight of stairs. Yet running upstairs is considered as doing work (in running downstairs, one gets work out of the world, according to physics), but in simply holding an object in a fixed position, no work is done. Clearly, the physical definition of work differs from the physiological definition, for reasons we shall briefly explore.

It is a fact that when one holds a weight he has to do “physiological” work. Why should he sweat? Why should he need to consume food to hold the weight up? Why is the machinery inside him operating at full throttle, just to hold the weight up? Actually, the weight could be held up with no effort by just placing it on a table; then the table, quietly and calmly, without any supply of energy, is able to maintain the same weight at the same height! The physiological situation is something like the following. There are two kinds of muscles in the human body and in other animals: one kind, called striated or skeletal muscle, is the type of muscle we have in our arms, for example, which is under voluntary control; the other kind, called smooth muscle, is like the muscle in the intestines or, in the clam, the greater adductor muscle that closes the shell. The smooth muscles work very slowly, but they can hold a “set”; that is to say, if the clam tries to close its shell in a certain position, it will hold that position, even if there is a very great force trying to change it. It will hold a position under load for hours and hours without getting tired because it is very much like a table holding up a weight, it “sets” into a certain position, and the molecules just lock there temporarily with no work being done, no effort being generated by the clam. The fact that we have to generate effort to hold up a weight is simply due to the design of striated muscle. What happens is that when a nerve impulse reaches a muscle fiber, the fiber gives a little twitch and then relaxes, so that when we hold something up, enormous volleys of nerve impulses are coming in to the muscle, large numbers of twitches are maintaining the weight, while the other fibers relax. We can see this, of course: when we hold a heavy weight and get tired, we begin to shake. The reason is that the volleys are coming irregularly, and the muscle is tired and not reacting fast enough. Why such an inefficient scheme? We do not know exactly why, but evolution has not been able to develop fast smooth muscle. Smooth muscle would be much more effective for holding up weights because you could just stand there and it would lock in; there would be no work involved and no energy would be required. However, it has the disadvantage that it is very slow-operating.

2025.10.24: This is wrong. 에너지/기 흐름에 대한 파인만 자신의 언급에 배치되는 work 정의 수정해야 ... physical work로 제한 내지 기 flow라 수정해야 한다는 말이다

1. No work does not mean not used up energy, 정확히 말해서 phyical work not equal to energy.

2. 10.25: 정확히 말하자면, 물건 드는 근육을 통해, 끊임없이 내려 물건에 가해지는 기들에 반대되는/떠받히는 기들이 전달된다는 거다, 작용-반작용과 마찬가지로.

2022.12.30: virtual work, rachet & pawl

Returning now to physics, we may ask why we want to calculate the work done. The answer is that it is interesting and useful to do so, since the work done on a particle by the resultant of all the forces acting on it is exactly equal to the change in kinetic energy of that particle. That is, if an object is being pushed, it picks up speed, and \begin{equation*} \Delta(v^2)=\frac{2}{m}\,\FLPF\cdot\Delta\FLPs. \end{equation*}

14–2Constrained motion

Another interesting feature of forces and work is this: suppose that we have a sloping or a curved track, and a particle that must move along the track, but without friction. Or we may have a pendulum with a string and a weight; the string constrains the weight to move in a circle about the pivot point. The pivot point may be changed by having the string hit a peg, so that the path of the weight is along two circles of different radii. These are examples of what we call fixed, frictionless constraints.

In motion with a fixed frictionless constraint, no work is done by the constraint because the forces of constraint are always at right angles to the motion. By the “forces of constraint” we mean those forces which are applied to the object directly by the constraint itself—the contact force with the track, or the tension in the string.

The forces involved in the motion of a particle on a slope moving under the influence of gravity are quite complicated, since there is a constraint force, a gravitational force, and so on. However, if we base our calculation of the motion on conservation of energy and the gravitational force alone, we get the right result. This seems rather strange, because it is not strictly the right way to do it—we should use the resultant force. Nevertheless, the work done by the gravitational force alone will turn out to be the change in the kinetic energy, because the work done by the constraint part of the force is zero (Fig. 14–1).

The important feature here is that if a force can be analyzed as the sum of two or more “pieces” then the work done by the resultant force in going along a certain curve is the sum of the works done by the various “component” forces into which the force is analyzed. Thus if we analyze the force as being the vector sum of several effects, gravitational plus constraint forces, etc., or the $x$-component of all forces and the $y$-component of all forces, or any other way that we wish to split it up, then the work done by the net force is equal to the sum of the works done by all the parts into which we have divided the force in making the analysis.

14–3Conservative forces

In nature there are certain forces, that of gravity, for example, which have a very remarkable property which we call “conservative” (no political ideas involved, it is again one of those “crazy words”). If we calculate how much work is done by a force in moving an object from one point to another along some curved path, in general the work depends upon the curve, but in special cases it does not. If it does not depend upon the curve, we say that the force is a conservative force. In other words, if the integral of the force times the distance in going from position $1$ to position $2$ in Fig. 14–2 is calculated along curve $A$ and then along $B$, we get the same number of joules, and if this is true for this pair of points on every curve, and if the same proposition works no matter which pair of points we use, then we say the force is conservative. In such circumstances, the work integral going from $1$ to $2$ can be evaluated in a simple manner, and we can give a formula for the result. Ordinarily it is not this easy, because we also have to specify the curve, but when we have a case where the work does not depend on the curve, then, of course, the work depends only upon the positions of $1$ and $2$.

2025.1.27: 경로에 따른 경우

4.9: 어떤 경로를 취하건 같은 양의 기들이 사용된다는 거...

아래위층 기의 양이 오르락 내리락 하며 평형 유지의 맥스웰 방정식을 보면, 기의 양을 일정하게 유지하는 전자는 양이 고정된 topological 틀로 보인다

To demonstrate this idea, consider the following. We take a “standard” point $P$, at an arbitrary location (Fig. 14–2). Then, the work line-integral from $1$ to $2$, which we want to calculate, can be evaluated as the work done in going from $1$ to $P$ plus the work done in going from $P$ to $2$, because the forces are conservative and the work does not depend upon the curve. Now, the work done in going from position $P$ to a particular position in space is a function of that position in space. Of course it really depends on $P$ also, but we hold the arbitrary point $P$ fixed permanently for the analysis. If that is done, then the work done in going from point $P$ to point $2$ is some function of the final position of $2$. It depends upon where $2$ is; if we go to some other point we get a different answer.

We shall call this function of position $-U(x,y,z)$, and when we wish to refer to some particular point $2$ whose coordinates are $(x_2,y_2,z_2)$, we shall write $U(2)$, as an abbreviation for $U(x_2,y_2,z_2)$. The work done in going from point $1$ to point $P$ can be written also by going the other way along the integral, reversing all the $d\FLPs$’s. That is, the work done in going from $1$ to $P$ is minus the work done in going from the point $P$ to $1$: \begin{equation*} \int_1^P\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=\int_P^1\FLPF\cdot(-d\FLPs)= -\int_P^1\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs. \end{equation*} Thus the work done in going from $P$ to $1$ is $-U(1)$, and from $P$ to $2$ the work is $-U(2)$. Therefore the integral from $1$ to $2$ is equal to $-U(2)$ plus [$-U(1)$ backwards], or $+U(1) - U(2)$: \begin{gather} U(1)=-\int_P^1\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs,\quad U(2)=-\int_P^2\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs,\notag\\[1.5ex] \label{Eq:I:14:1} \int_1^2\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=U(1)-U(2). \end{gather} The quantity $U(1) - U(2)$ is called the change in the potential energy, and we call $U$ the potential energy. We shall say that when the object is located at position $2$, it has potential energy $U(2)$ and at position $1$ it has potential energy $U(1)$. If it is located at position $P$, it has zero potential energy. If we had used any other point, say $Q$, instead of $P$, it would turn out (and we shall leave it to you to demonstrate) that the potential energy is changed only by the addition of a constant. Since the conservation of energy depends only upon changes, it does not matter if we add a constant to the potential energy. Thus the point $P$ is arbitrary.

Now, we have the following two propositions: (1) that the work done by a force is equal to the change in kinetic energy of the particle, but (2) mathematically, for a conservative force, the work done is minus the change in a function $U$ which we call the potential energy. As a consequence of these two, we arrive at the proposition that if only conservative forces act, the kinetic energy $T$ plus the potential energy $U$ remains constant: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:2} T+U=\text{constant}. \end{equation}

Let us now discuss the formulas for the potential energy for a number of cases. If we have a gravitational field that is uniform, if we are not going to heights comparable with the radius of the earth, then the force is a constant vertical force and the work done is simply the force times the vertical distance. Thus \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:3} U(z)=mgz, \end{equation} and the point $P$ which corresponds to zero potential energy happens to be any point in the plane $z=0$. We could also have said that the potential energy is $mg(z - 6)$ if we had wanted to—all the results would, of course, be the same in our analysis except that the value of the potential energy at $z = 0$ would be $-6mg$. It makes no difference, because only differences in potential energy count.

The energy needed to compress a linear spring a distance $x$ from an equilibrium point is \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:4} U(x)=\tfrac{1}{2}kx^2, \end{equation} and the zero of potential energy is at the point $x=0$, the equilibrium position of the spring. Again we could add any constant we wish.

The potential energy of gravitation for point masses $M$ and $m$, a distance $r$ apart, is \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:5} U(r) = -GMm/r. \end{equation} The constant has been chosen here so that the potential is zero at infinity. Of course the same formula applies to electrical charges, because it is the same law: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:6} U(r) = q_1q_2/4\pi\epsO r. \end{equation}

Now let us actually use one of these formulas, to see whether we understand what it means. Question: How fast do we have to shoot a rocket away from the earth in order for it to leave? Solution: The kinetic plus potential energy must be a constant; when it “leaves,” it will be millions of miles away, and if it is just barely able to leave, we may suppose that it is moving with zero speed out there, just barely going. Let $a$ be the radius of the earth, and $M$ its mass. The kinetic plus potential energy is then initially given by $\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2 - GmM/a$. At the end of the motion the two energies must be equal. The kinetic energy is taken to be zero at the end of the motion, because it is supposed to be just barely drifting away at essentially zero speed, and the potential energy is $GmM$ divided by infinity, which is zero. So everything is zero on one side and that tells us that the square of the velocity must be $2GM/a$. But $GM/a^2$ is what we call the acceleration of gravity, $g$. Thus \begin{equation*} v^2=2ga. \end{equation*}

At what speed must a satellite travel in order to keep going around the earth? We worked this out long ago and found that $v^2 = GM/a$. Therefore to go away from the earth, we need $\sqrt{2}$ times the velocity we need to just go around the earth near its surface. We need, in other words, twice as much energy (because energy goes as the square of the velocity) to leave the earth as we do to go around it. Therefore the first thing that was done historically with satellites was to get one to go around the earth, which requires a speed of five miles per second. The next thing was to send a satellite away from the earth permanently; this required twice the energy, or about seven miles per second.

Now, continuing our discussion of the characteristics of potential energy, let us consider the interaction of two molecules, or two atoms, two oxygen atoms for instance. When they are very far apart, the force is one of attraction, which varies as the inverse seventh power of the distance, and when they are very close the force is a very large repulsion. If we integrate the inverse seventh power to find the work done, we find that the potential energy $U$, which is a function of the radial distance between the two oxygen atoms, varies as the inverse sixth power of the distance for large distances.

If we sketch the curve of the potential energy $U(r)$ as in Fig. 14–3, we thus start out at large $r$ with an inverse sixth power, but if we come in sufficiently near we reach a point $d$ where there is a minimum of potential energy. The minimum of potential energy at $r = d$ means this: if we start at $d$ and move a small distance, a very small distance, the work done, which is the change in potential energy when we move this distance, is nearly zero, because there is very little change in potential energy at the bottom of the curve. Thus there is no force at this point, and so it is the equilibrium point. Another way to see that it is the equilibrium point is that it takes work to move away from $d$ in either direction. When the two oxygen atoms have settled down, so that no more energy can be liberated from the force between them, they are in the lowest energy state, and they will be at this separation $d$. This is the way an oxygen molecule looks when it is cold. When we heat it up, the atoms shake and move farther apart, and we can in fact break them apart, but to do so takes a certain amount of work or energy, which is the potential energy difference between $r = d$ and $r=\infty$. When we try to push the atoms very close together the energy goes up very rapidly, because they repel each other.

The reason we bring this out is that the idea of force is not particularly suitable for quantum mechanics; there the idea of energy is most natural. We find that although forces and velocities “dissolve” and disappear when we consider the more advanced forces between nuclear matter and between molecules and so on, the energy concept remains. Therefore we find curves of potential energy in quantum mechanics books, but very rarely do we ever see a curve for the force between two molecules, because by that time people who are doing analyses are thinking in terms of energy rather than of force.

Next we note that if several conservative forces are acting on an object at the same time, then the potential energy of the object is the sum of the potential energies from each of the separate forces. This is the same proposition that we mentioned before, because if the force can be represented as a vector sum of forces, then the work done by the total force is the sum of the works done by the partial forces, and it can therefore be analyzed as changes in the potential energies of each of them separately. Thus the total potential energy is the sum of all the little pieces.

We could generalize this to the case of a system of many objects interacting with one another, like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, etc., or oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, etc., which are acting with respect to one another in pairs due to forces all of which are conservative. In these circumstances the kinetic energy in the entire system is simply the sum of the kinetic energies of all of the particular atoms or planets or whatever, and the potential energy of the system is the sum, over the pairs of particles, of the potential energy of mutual interaction of a single pair, as though the others were not there. (This is really not true for molecular forces, and the formula is somewhat more complicated; it certainly is true for Newtonian gravitation, and it is true as an approximation for molecular forces. For molecular forces there is a potential energy, but it is sometimes a more complicated function of the positions of the atoms than simply a sum of terms from pairs.) In the special case of gravity, therefore, the potential energy is the sum, over all the pairs $i$ and $j$, of $-Gm_im_j/r_{ij}$, as was indicated in Eq. (13.14). Equation (13.14) expressed mathematically the following proposition: that the total kinetic energy plus the total potential energy does not change with time. As the various planets wheel about, and turn and twist and so on, if we calculate the total kinetic energy and the total potential energy we find that the total remains constant.

14–4Nonconservative forces

We have spent a considerable time discussing conservative forces; what about nonconservative forces? We shall take a deeper view of this than is usual, and state that there are no nonconservative forces! As a matter of fact, all the fundamental forces in nature appear to be conservative. This is not a consequence of Newton’s laws. In fact, so far as Newton himself knew, the forces could be nonconservative, as friction apparently is. When we say friction apparently is, we are taking a modern view, in which it has been discovered that all the deep forces, the forces between the particles at the most fundamental level, are conservative.

If, for example, we analyze a system like that great globular star cluster that we saw a picture of, with the thousands of stars all interacting, then the formula for the total potential energy is simply one term plus another term, etc., summed over all pairs of stars, and the kinetic energy is the sum of the kinetic energies of all the individual stars. But the globular cluster as a whole is drifting in space too, and, if we were far enough away from it and did not see the details, could be thought of as a single object. Then if forces were applied to it, some of those forces might end up driving it forward as a whole, and we would see the center of the whole thing moving. On the other hand, some of the forces can be, so to speak, “wasted” in increasing the kinetic or potential energy of the “particles” inside. Let us suppose, for instance, that the action of these forces expands the whole cluster and makes the particles move faster. The total energy of the whole thing is really conserved, but seen from the outside with our crude eyes which cannot see the confusion of motions inside, and just thinking of the kinetic energy of the motion of the whole object as though it were a single particle, it would appear that energy is not conserved, but this is due to a lack of appreciation of what it is that we see. And that, it turns out, is the case: the total energy of the world, kinetic plus potential, is a constant when we look closely enough.

When we study matter in the finest detail at the atomic level, it is not always easy to separate the total energy of a thing into two parts, kinetic energy and potential energy, and such separation is not always necessary. It is almost always possible to do it, so let us say that it is always possible, and that the potential-plus-kinetic energy of the world is constant. Thus the total potential-plus-kinetic energy inside the whole world is constant, and if the “world” is a piece of isolated material, the energy is constant if there are no external forces. But as we have seen, some of the kinetic and potential energy of a thing may be internal, for instance the internal molecular motions, in the sense that we do not notice it. We know that in a glass of water everything is jiggling around, all the parts are moving all the time, so there is a certain kinetic energy inside, which we ordinarily may not pay any attention to. We do not notice the motion of the atoms, which produces heat, and so we do not call it kinetic energy, but heat is primarily kinetic energy. Internal potential energy may also be in the form, for instance, of chemical energy: when we burn gasoline energy is liberated because the potential energies of the atoms in the new atomic arrangement are lower than in the old arrangement. It is not strictly possible to treat heat as being pure kinetic energy, for a little of the potential gets in, and vice versa for chemical energy, so we put the two together and say that the total kinetic and potential energy inside an object is partly heat, partly chemical energy, and so on. Anyway, all these different forms of internal energy are sometimes considered as “lost” energy in the sense described above; this will be made clearer when we study thermodynamics.

As another example, when friction is present it is not true that kinetic energy is lost, even though a sliding object stops and the kinetic energy seems to be lost. The kinetic energy is not lost because, of course, the atoms inside are jiggling with a greater amount of kinetic energy than before, and although we cannot see that, we can measure it by determining the temperature. Of course if we disregard the heat energy, then the conservation of energy theorem will appear to be false.

Another situation in which energy conservation appears to be false is when we study only part of a system. Naturally, the conservation of energy theorem will appear not to be true if something is interacting with something else on the outside and we neglect to take that interaction into account.

In classical physics potential energy involved only gravitation and electricity, but now we have nuclear energy and other energies also. Light, for example, would involve a new form of energy in the classical theory, but we can also, if we want to, imagine that the energy of light is the kinetic energy of a photon, and then our formula (14.2) would still be right.

14–5Potentials and fields

We shall now discuss a few of the ideas associated with potential energy and with the idea of a field. Suppose we have two large objects $A$ and $B$ and a third very small one which is attracted gravitationally by the two, with some resultant force $\FLPF$. We have already noted in Chapter 12 that the gravitational force on a particle can be written as its mass, $m$, times another vector, $\FLPC$, which is dependent only upon the position of the particle: \begin{equation*} \FLPF=m\FLPC. \end{equation*} We can analyze gravitation, then, by imagining that there is a certain vector $\FLPC$ at every position in space which “acts” upon a mass which we may place there, but which is there itself whether we actually supply a mass for it to “act” on or not. $\FLPC$ has three components, and each of those components is a function of $(x,y,z)$, a function of position in space. Such a thing we call a field, and we say that the objects $A$ and $B$ generate the field, i.e., they “make” the vector $\FLPC$. When an object is put in a field, the force on it is equal to its mass times the value of the field vector at the point where the object is put.

We can also do the same with the potential energy. Since the potential energy, the integral of $(-\textbf{force})\cdot(d\FLPs)$ can be written as $m$ times the integral of $(-\textbf{field})\cdot(d\FLPs)$, a mere change of scale, we see that the potential energy $U(x,y,z)$ of an object located at a point $(x,y,z)$ in space can be written as $m$ times another function which we may call the potential $\Psi$. The integral $\int\FLPC\cdot d\FLPs=-\Psi$, just as $\int\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=-U$; there is only a scale factor between the two: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:7} U=-\int\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=-m\int\FLPC\cdot d\FLPs=m\Psi. \end{equation} By having this function $\Psi(x,y,z)$ at every point in space, we can immediately calculate the potential energy of an object at any point in space, namely, $U(x, y, z) = m\Psi(x, y, z)$—rather a trivial business, it seems. But it is not really trivial, because it is sometimes much nicer to describe the field by giving the value of $\Psi$ everywhere in space instead of having to give $\FLPC$. Instead of having to write three complicated components of a vector function, we can give instead the scalar function $\Psi$. Furthermore, it is much easier to calculate $\Psi$ than any given component of $\FLPC$ when the field is produced by a number of masses, for since the potential is a scalar we merely add, without worrying about direction. Also, the field $\FLPC$ can be recovered easily from $\Psi$, as we shall shortly see. Suppose we have point masses $m_1$, $m_2$, … at the points $1$, $2$, … and we wish to know the potential $\Psi$ at some arbitrary point $p$. This is simply the sum of the potentials at $p$ due to the individual masses taken one by one: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:8} \Psi(p)=\sum_i-\frac{Gm_i}{r_{ip}},\quad i=\text{$1$, $2$, $\ldots$} \end{equation}

In the last chapter we used this formula, that the potential is the sum of the potentials from all the different objects, to calculate the potential due to a spherical shell of matter by adding the contributions to the potential at a point from all parts of the shell. The result of this calculation is shown graphically in Fig. 14–4. It is negative, having the value zero at $r = \infty$ and varying as $1/r$ down to the radius $a$, and then is constant inside the shell. Outside the shell the potential is $-Gm/r$, where $m$ is the mass of the shell, which is exactly the same as it would have been if all the mass were located at the center. But it is not everywhere exactly the same, for inside the shell the potential turns out to be $-Gm/a$, and is a constant! When the potential is constant, there is no field, or when the potential energy is constant there is no force, because if we move an object from one place to another anywhere inside the sphere the work done by the force is exactly zero. Why? Because the work done in moving the object from one place to the other is equal to minus the change in the potential energy (or, the corresponding field integral is the change of the potential). But the potential energy is the same at any two points inside, so there is zero change in potential energy, and therefore no work is done in going between any two points inside the shell. The only way the work can be zero for all directions of displacement is that there is no force at all.

This gives us a clue as to how we can obtain the force or the field, given the potential energy. Let us suppose that the potential energy of an object is known at the position $(x,y,z)$ and we want to know what the force on the object is. It will not do to know the potential at only this one point, as we shall see; it requires knowledge of the potential at neighboring points as well. Why? How can we calculate the $x$-component of the force? (If we can do this, of course, we can also find the $y$- and $z$-components, and we will then know the whole force.) Now, if we were to move the object a small distance $\Delta x$, the work done by the force on the object would be the $x$-component of the force times $\Delta x$, if $\Delta x$ is sufficiently small, and this should equal the change in potential energy in going from one point to the other: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:9} \Delta W=-\Delta U=F_x\,\Delta x. \end{equation} We have merely used the formula $\int\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=-\Delta U$, but for a very short path. Now we divide by $\Delta x$ and so find that the force is \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:10} F_x=-\Delta U/\Delta x. \end{equation}

Of course this is not exact. What we really want is the limit of (14.10) as $\Delta x$ gets smaller and smaller, because it is only exactly right in the limit of infinitesimal $\Delta x$. This we recognize as the derivative of $U$ with respect to $x$, and we would be inclined, therefore, to write $-dU/dx$. But $U$ depends on $x$, $y$, and $z$, and the mathematicians have invented a different symbol to remind us to be very careful when we are differentiating such a function, so as to remember that we are considering that only $x$ varies, and $y$ and $z$ do not vary. Instead of a $d$ they simply make a “backwards $6$,” or $\partial$. (A $\partial$ should have been used in the beginning of calculus because we always want to cancel that $d$, but we never want to cancel a $\partial$!) So they write $\ddpl{U}{x}$, and furthermore, in moments of duress, if they want to be very careful, they put a line beside it with a little $yz$ at the bottom ($\ddpl{U}{x}|_{yz}$), which means “Take the derivative of $U$ with respect to $x$, keeping $y$ and $z$ constant.” Most often we leave out the remark about what is kept constant because it is usually evident from the context, so we usually do not use the line with the $y$ and $z$. However, always use a $\partial$ instead of a $d$ as a warning that it is a derivative with some other variables kept constant. This is called a partial derivative; it is a derivative in which we vary only $x$.

Therefore, we find that the force in the $x$-direction is minus the partial derivative of $U$ with respect to $x$: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:11} F_x=-\ddpl{U}{x}. \end{equation} In a similar way, the force in the $y$-direction can be found by differentiating $U$ with respect to $y$, keeping $x$ and $z$ constant, and the third component, of course, is the derivative with respect to $z$, keeping $y$ and $x$ constant: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:12} F_y=-\ddpl{U}{y},\quad F_z=-\ddpl{U}{z}. \end{equation} This is the way to get from the potential energy to the force. We get the field from the potential in exactly the same way: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:13} C_x=-\ddpl{\Psi}{x},\quad C_y=-\ddpl{\Psi}{y},\quad C_z=-\ddpl{\Psi}{z}. \end{equation}

Incidentally, we shall mention here another notation, which we shall not actually use for quite a while: Since $\FLPC$ is a vector and has $x$-, $y$-, and $z$-components, the symbolized $\ddpl{}{x}$, $\ddpl{}{y}$, and $\ddpl{}{z}$ which produce the $x$-, $y$-, and $z$-components are something like vectors. The mathematicians have invented a glorious new symbol, $\FLPnabla$, called “grad” or “gradient”, which is not a quantity but an operator that makes a vector from a scalar. It has the following “components”: The $x$-component of this “grad” is $\ddpl{}{x}$, the $y$-component is $\ddpl{}{y}$, and the $z$-component is $\ddpl{}{z}$, and then we have the fun of writing our formulas this way: \begin{equation} \label{Eq:I:14:14} \FLPF=-\FLPgrad{U},\quad \FLPC=-\FLPgrad{\Psi}. \end{equation} Using $\FLPnabla$ gives us a quick way of testing whether we have a real vector equation or not, but actually Eqs. (14.14) mean precisely the same as Eqs. (14.11), (14.12) and (14.13); it is just another way of writing them, and since we do not want to write three equations every time, we just write $\FLPgrad{U}$ instead.

One more example of fields and potentials has to do with the electrical case. In the case of electricity the force on a stationary object is the charge times the electric field: $\FLPF = q\FLPE$. (In general, of course, the $x$-component of force in an electrical problem has also a part which depends on the magnetic field. It is easy to show from Eq. (12.11) that the force on a particle due to magnetic fields is always at right angles to its velocity, and also at right angles to the field. Since the force due to magnetism on a moving charge is at right angles to the velocity, no work is done by the magnetism on the moving charge because the motion is at right angles to the force. Therefore, in calculating theorems of kinetic energy in electric and magnetic fields we can disregard the contribution from the magnetic field, since it does not change the kinetic energy.) We suppose that there is only an electric field. Then we can calculate the energy, or work done, in the same way as for gravity, and calculate a quantity $\phi$ which is minus the integral of $\FLPE\cdot d\FLPs$, from the arbitrary fixed point to the point where we make the calculation, and then the potential energy in an electric field is just charge times this quantity $\phi$: \begin{gather*} \phi(\FLPr)=-\int\FLPE\cdot d\FLPs,\\[1ex] U=q\phi. \end{gather*}

Let us take, as an example, the case of two parallel metal plates, each with a surface charge of $\pm\sigma$ per unit area. This is called a parallel-plate capacitor. We found previously that there is zero force outside the plates and that there is a constant electric field between them, directed from $+$ to $-$ and of magnitude $\sigma/\epsO$ (Fig. 14–5). We would like to know how much work would be done in carrying a charge from one plate to the other. The work would be the $(\textbf{force})\cdot(d\FLPs)$ integral, which can be written as charge times the potential value at plate $1$ minus that at plate $2$: \begin{equation*} W=\int_1^2\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=q(\phi_1-\phi_2). \end{equation*} We can actually work out the integral because the force is constant, and if we call the separation of the plates $d$, then the integral is easy: \begin{equation*} \int_1^2\FLPF\cdot d\FLPs=\frac{q\sigma}{\epsO}\int_1^2dx= \frac{q\sigma d}{\epsO}. \end{equation*} The difference in potential, $\Delta\phi=\sigma d/\epsO$, is called the voltage difference, and $\phi$ is measured in volts. When we say a pair of plates is charged to a certain voltage, what we mean is that the difference in electrical potential of the two plates is so-and-so many volts. For a capacitor made of two parallel plates carrying a surface charge $\pm\sigma$, the voltage, or difference in potential, of the pair of plates is $\sigma d/\epsO$.